We are sharing tales from the MST as hikers are pursuing the 40 Hike Challenge.

This week we are exploring the Great Day Hike #01 in Segment 1, The Great Smokies: Clingmans Done to Fork Ridge Trail, hiked by Liz and Paul Hosier

Mile 0. The MST. The trek from the summit of Clingmans Dome on the NC/TN state line to Fork Ridge Trail, about 4 miles distant, is a fitting start to the North Carolina trail that promises views of the entire state’s diverse geologic setting, sightings of fascinating flora and fauna, and an experience with NC’s ever-changing and often dramatic weather conditions. It is a challenge to a hiker’s skills and stamina, to boot! Clingmans Dome (6,642 ft) provides a stunning, unobstructed view of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park and several surrounding states. Notably, Clingmans Dome is the third highest peak in eastern North America, just a few feet shorter than Mt. Mitchell (6,684 ft) and Mt. Craig (6,647 ft), both found in North Carolina’s Black Mountains east of Clingmans Dome.

Designated Hike #1, the Clingmans Dome to Fork Ridge Trail segment begins with a continuous downhill stretch from Clingmans Dome to Mt. Collins Gap. About 3 1/2 miles into the hike, the trail ascends to the crest of Mt. Collins (6,188 ft), followed by a short downhill segment that reaches Clingmans Dome Access Road, the road we traveled to reach Clingmans Dome and the trek’s start. After crossing the road, the MST plunges almost 3,000 feet to where Fork Ridge Trail meets Deep Creek Trail and, eventually, the Oconaluftee Visitors Center.

To begin our trek, we parked one vehicle where the MST crosses Clingmans Dome Access Road (Fork Ridge trailhead). Then we drove to Clingmans Dome parking lot and parked a second car there. From the parking lot, we followed the roughly 1/2 mile macadam path to the observation tower atop Clingmans Dome.

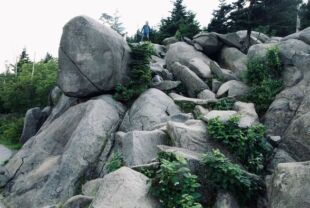

At the beginning of the walk to the observation tower, we noted the large, rock outcrop the right. This fine-grained, hard, gray rock, underlies much of Clingmans Dome and explains, at least in part, why this mountain resists erosion and therefore remains the highest point of the Great Smoky Mountains.

Wildflowers and grasses line the path to the tower and they welcomed us to the trail with random splotches of vibrant colors: reds, yellows, greens and browns.

We began our hike in mid morning, a time when only a few people were walking up the access trail to the top of Clingmans Dome. A handful carried large backpacks suggesting that they were trekking well beyond the observation tower. Later in the day, when we returned to the parking lot to retrieve our car, this same walkway was jammed with hundreds of people walking up to the observation tower.

Once we reached the crest of Clingmans Dome, we continued our walk to the top of the observation platform that towers over the trees. Here one can view the spruce and fir forests immediately below the tower as well as the hardwood forests that cover most of the distant mountains. On a clear day, you are surrounded by breathtaking and dramatic views of the Great Smoky Mountains and seemingly unending mountain ranges beyond. Mt. LeConte stands nearly as high as Clingmans Dome just few miles northeast, while Newton Bald and the more distant Waterrock Knob dominate views toward the southeast. On the day of our trek, a dense morning fog hung over the dome and the only visible features were the persons standing next to us!

Returning to the base of the observation tower, we located the post and signs for the MST. The Appalachian Trail crosses Clingmans Dome at the base of the observation tower and the MST begins here. Starting here, the MST and Appalachian Trail are confluent for nearly the entire length of Hike #1. Other than the MST starting post, there are not many blazes for MST (a small white circle) but following the initial MST directional arrow and the large rectangular Appalachian Trail blazes will be sure to head you in the right direction.

Our trek began in a dense, somewhat dark, forest dominated exclusively by the needle-leaved evergreen, Fraser fir, a Southern Appalachian Mountain endemic tree. As we descended through the fir forest, we began to see other tree species, in particular red spruce, also an evergreen species. Within a half hour’s walk (and several hundred feet lower elevation), broadleaved trees— red maple, yellow birch and mountain ash—joined Fraser fir and red spruce in the overstory. Because the predominantly evergreen overstory attenuates much of the sunlight, few shrubs grow in the fir and spruce forests; however, hobblebush is an exception. It is common throughout high elevation forests in the Smokies especially where fallen trees open the canopy and allow sunlight to reach the forest floor.

Fraser fir and red spruce forests are typically cool and damp, a condition generated by the near ubiquity of water. Extraordinarily high rainfall, frequent and dense fog, and copious quantities of groundwater flowing beneath the thin soils contribute to the high moisture near the mountaintops. The evergreen trees grow in dense patches and attenuate sunlight so much that it is difficult to take good photographs.

Observing the forest along either side of the trail from the beginning to the end of this hike, Liz and I noticed myriad fallen trees—literally hundreds, if not thousands, of toppled trees along the length of this hike. The death of nearly all of the largest and oldest Fraser firs has been caused by the balsam woolly adelgid, a non-native insect, introduced into this area in the 1950s. Over time, sapling-sized firs quickly fill the open, sunlit spaces created as the diseased trees die and topple out of the canopy. The trees fall in all directions, often one atop another, and form a jumble of horizontal trunks resembling a giant pile of “pick up sticks,” a pile one creates at the start of the children’s game with the same name.

Fog frequently shrouds the mountaintops and slopes of the Blue Ridge. This creates a super moist environment within the forest which supports the growth of many plants dependent on high atmospheric moisture: ferns, mosses, lichens, fungi and algae. Representatives of one or another of these organisms cover seemingly every square inch of exposed rock, soil, and living as well as dead trees—including the trunks and branches of overstory and understory trees.

The diversity of these plants found in the Fraser fir and red spruce forest habitat is spectacular. As we trekked through the forest, we observed an immense variety of intricate shapes, range of sizes, interesting structural patterns, and diverse color palate of these moisture-loving plants. In dramatic contrast, seasonal wild flowers, so abundant in lower elevation hardwood forests, are much less common in the moist evergreen forests due, in part, to the reduced sunlight reaching the ground in the Fraser fir and red spruce forests when compared to the hardwood forests.

We found the trail on this hike well established and well cared for by attentive trail maintainers. This attention to the trail makes this first MST hike especially enjoyable. Especially near the top of Clingmans Dome, constant foot traffic and water erosion has created a trail that has lost a few inches of soil, exposing the bedrock in some places. When trekking through a rainstorm or very wet weather, you may encounter tiny streams along parts of the trail where water temporarily flows in the center of the trail. To reduce this, trail maintainers have installed many water bars to move water away from the trail tread. We encountered no extensive boggy or persistently wet areas along the MST Hike #1. Surface water moves off the trail within hours after it falls and, on dry days, the trail exhibits no water accumulation.

As we descended from Mt. Collins, we reached a crossroads with directional and distance signage. The Mt. Collins overnight AT shelter is 1/2 mile to the left while the AT and MST continue to the right. In a short distance, the AT turns left toward Newfound Gap, several miles away. Continuing on the MST, we reached the Clingmans Dome Access Road and the beginning of Fork Ridge Trail where the MST continues into the Deep Creek watershed. From here, we returned to Clingmans Dome to retrieve our car.

Shortly after we began our trek today, we encountered three women carrying full packs. We engaged them in “trail talk” and they indicated that they plan to hike the entire MST and said it was only logical to start at the beginning! So here they were, on their first day of a multi-day hike planning to cover more than 10 miles of their 40-plus MST trail miles from Clingmans Dome to Waterrock Knob.

Courtney, Malia and Emily are thrilled to have the opportunity to hike the MST. They are good friends and said that they are looking forward to sharing the experience with one another. We memorialized their first day on the MST with a photograph of the trio. You can tell by their broad smiles, they are delighted to be away from the serious concerns of the day and eagerly look forward to time together on the MST.

For Courtney, Malia and Emily, this happy first day will be repeated over and over until they reach NC’s coast where it will be a momentous and thrilling day when they complete the MST. Liz and I hope that someone will be at Jockeys Ridge when they arrive and similarly memorialize their joyful last day on the MST. Best wishes, Courtney, Malia and Emily! We wish you godspeed on your MST journey, a trek that is certain to solidify friendships and allow you to discover the extensive natural and cultural histories of North Carolina.

In a short distance, the AT turns left toward Newfound Gap, several miles away. Continuing on the MST, we reached the Clingmans Dome Access Road and the beginning of Fork Ridge Trail where the MST continues into the Deep Creek watershed. From here, we returned to Clingmans Dome to retrieve our car.

Paul Hosier is a coastal plant ecologist and long-time MST member. He was a professor of biology at UNC-Wilmington for 41 years and is currently a professor emeritus there. He taught general ecology, barrier island ecology, and coastal management. Paul has conducted research along the coasts of NC, SC and GA to study the effects of hurricanes on vegetation, the effects of off-road vehicles on coastal processes and vegetation, and many other studies that were integral to the understanding of coastal systems. He is the author of Seacoast Plants of the Carolinas; A New Guide for Plant Identification and Use in the Coastal Landscape.

We invite you to hike all 40 of the hikes in Great Day Hikes – take the 40 Hike Challenge! If you’ve hiked one of the 40 Hikes, share your story with us. Hashtag #MST40Hike or email with your tale.